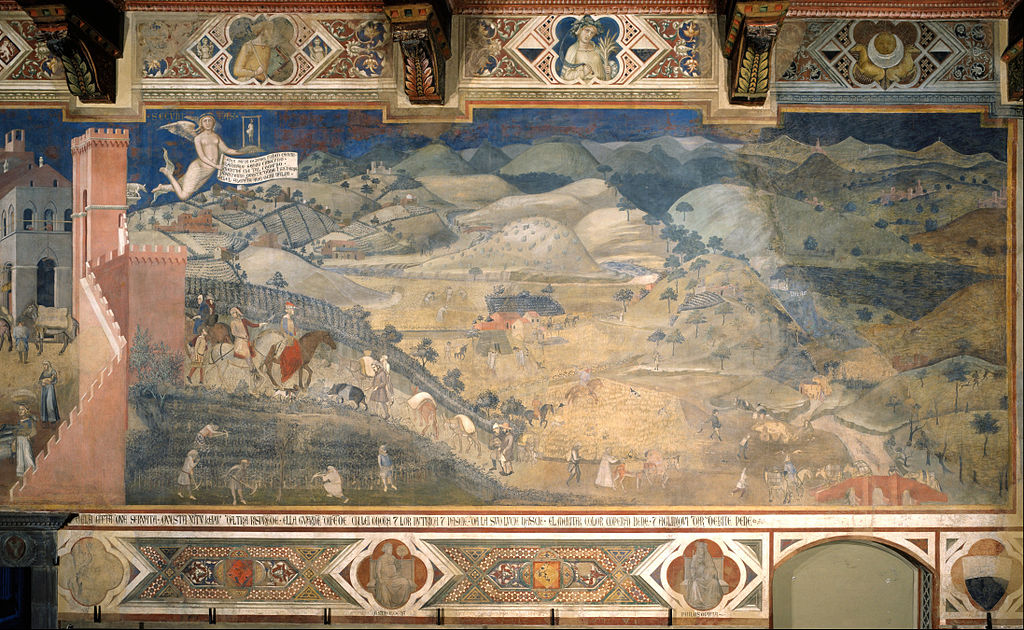

Giovanna Tiezzi’s land south of Siena in Tuscany, looks much like it did a thousand years ago with woods, vineyards, olive trees, legumes and grains in a patchwork that spreads across gently rolling hills. “You can do down to the Municipal Palace in Siena and see it in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fresco “The Allegory of Good and Bad Government” from 1380,” she told me. “It hasn’t changed. My husband, Stefano and I feel that we are stewards of this land. It’s our duty to make wine that expresses all that Nature has given us.”

The land originally belonged to a monastery constructed around the year 900. Pacina’s home, cantina and various family members’ apartments are in the monastery now. “We have a community of friends and family here,” Giovanna said. I followed her out between the ancient walls and massive shade trees in the garden.

We went out through the gates at the other end, and continued along the dirt road that divides Pacina (from the Etruscan name of this place) like a long spine with soft slopes falling away on both sides. “Look up there,” Giovanna pointed north, “and you can see the steeper hills of Chianti Classico. We don’t have to choose one side of the hill like they do. Here, the plants have exposure to the sun from all directions, and there is always wind [that keeps them free of humidity and mold].”

In short, Nature has blessed Pacina with practically ideal conditions. “It would be a crime to use chemical treatments here,” Giovanna explained as she stood among her oldest vines planted just after the Second World War.

“Maybe in places where there is lots of humidity, bad soil, no wind….but not here where Nature has offered us the best of everything. If we treat it well, like a good friend, it will give back.” (Pacina has been farmed organically since the early eighties.)

She was referring not just to the climate, but also the soil and the Sangiovese grape variety. Millions of years ago, Pacina was under the sea. Giovanna has a collection of fossilized shells from the vineyards. The white soil is a mixture of sandy limestone and clay called “Tufo di Siena”. It drains quickly and gives a lot of minerality to the wine. As for Sangiovese, Giovanna calls it a “princely variety” that “bites your tongue”, with lots of acidity and noble tannins. It is both pleasing to drink and able to age well.

Giovanna pointed out that her oldest vines, planted just after World War II, don’t require nearly as much attention as the young ones. “They are like old people,” she said laughing a little, “They have found balance and know how to behave. In fact, they do better if I don’t intervene. They know exactly what they need to do to produce excellent grapes.”

She sighed, smiled again, and walked into a newer vineyard. “On the other hand, I really have to work to train these young ones. I have to be attentive, the way you care for young children.”

Giovanna has 60 hectares but only ten are planted with vines.

The rest are either woodlands or fields, planted with chick peas, spelt, and olive trees.

The farm is worked using not only organic but biodynamic principles. There are animals, chickens, ducks, geese, etc.

Outlying buildings have been restored to make a lovely bed and breakfast for vineyard stays.

And then, there is the cantina in the monastery. Giovanna pushed the huge, antique doors open and said, “It’s all very simple, built in the thirties. We ferment the wine with indigenous yeasts in these cement tanks. Nothing is added (not even sulfites). There is no temperature control, no clarification, no filtering. The grapes decide what to do. They make the wine. I don’t.”

She went on to say that the process of fermentation truly is a miracle, something she trusts and doesn’t try to control. Listening to Giovanna, I thought of the ancients, who believed that wine was “di-vine” (literally, “of the vine”), not made by man but made by the gods.

After fermentation, Pacina wines go into barrels and, then, bottles in the underground cellar, which maintains its temperature naturally. It is actually a passageway that runs the length of the monastery.

“We don’t dare clean anything down here,” she said. “The cellar is full of natural yeasts.”

It was cool and dark but didn’t smell musty at all. I had the feeling that a monk might step out from the shadows at any moment as we passed through the winding labyrinth of corridors and rooms.

We popped up at the other end of the monastery in the rooms where Giovanna, Stefano and their children live. The art, spaces and furnishings evoke both elegance and a long family tradition of living on the land: both of which came out in the wine.

Giovanna showed me her father’s bottle from 1969 and how much it looks like hers. “This is not a business for us,” she said, “We make ends meet, but we are not interested in using the land to get rich. We are stewards of the land for now. Then, we will pass it on to future generations. It doesn’t really belong to us. We belong to it.” Pacina wines are classified IGT. “We left the DOC because all of the laws that are supposed to protect tradition, culture and excellence are doing the opposite.”

Giovanna is one of many “natural” vintners to make this choice. She and Pacina were recently featured in Jonathon Nossitor’s film, Natural Resistance. Order on Amazon. See on Facebook. Watch trailer.

Find Pacina wines on Wine Searcher. In the range of $25-30.

Pacina

Località Pacina, 7

Castelnuovo Berardenga (SI)

40,000 bottles annually

Pacina is part of FIVI: Federation of Independent Winegrowers